EPHEMERALITY, DOCUMENTATION + THE HOUSE

May 2013

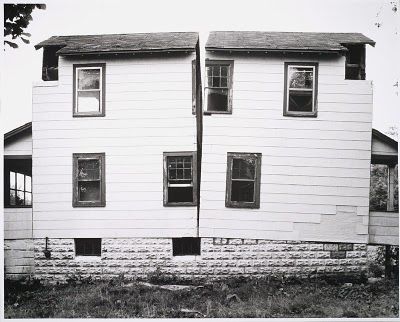

In the early 1970s as a young Australian art student, during the ‘Americanisation’ of our art scene, when painting was the predominant art form, I happened upon an arresting image of a house that had been cut into two. The image was of Gordon Matta-Clark’s Splitting (in Englewood) 1974. “Matta-Clark cut in half a New Jersey house from which the tenants had been abruptly evicted to make room for a planned (but never finished) urban renewal project”. (1) This strange image which has resonated over the years, was of an ordinary American two storey weatherboard house with a ‘gash’, a split down its side facades, gapping several feet apart at the roof and tapering down towards the brick foundations. This image was the first art work that introduced me to the concept that the house structure, the facade, as opposed to the emotive ‘home’ the internalisation of the house, could be a suitable subject for serious contemporary art. But it took me another twenty years, to actualise this important early realisation, when I too started using the ‘house’ as the basis for sculpture. I also intrinsically understand the joy, the catharsis of demolition!

Gordon Matta-Clark: Splitting (in Englewood) 1974

Image source: www.artnet.com courtesy David Zwirner N.Y. and Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark

The artists who are discussed in this article are Gordon Matta-Clark, Rachel Whiteread, and Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro. All the artists, have transformed existing houses, houses slated for demolition in the name of urban renewal, into temporary sculptural installations, except for Healy and Cordeiro’s Not Under My Roof . These houses, objet trouvé, were non-art objects but they provided the raw material for the artists to transform them physically and philosophically into profound art works. However, by the very nature of these transient art objects they are now only memories for those who actually experienced. And for the rest of us, we can only know them through documentation in drawings, photographs, films and videos. Notwithstanding, John Berger says: “a photograph whilst recording what has been seen, always and by its nature refers to what is not seen. It isolates, preserves and presents a moment taken from a continuum”.(2)

Contemporary artists who involve themselves with issues about the house use sculpture both on the monumental and intimate scales, to express their concerns and insights into how we experience ‘dwelling’ in this modern world.

The house is an extension of the person, like an extra skin, carapace or second layer of cloths, it serves as much to reveal and display as it does to hide and protect. House, body and mind are in continuous interaction, the physical structure, furnishings, social conventions and mental images of the house at once enabling, moulding, informing and constraining the activities and ideas which unfold within its bounds. (3)

GORDON MATTA-CLARK

Matta-Clark went to Cornell University to study architecture from 1962 -1968, which was then very much a modernist architectural stronghold, espousing the philosophies of Le Corbusier. He graduated but never practised as an architect. Instead, he used buildings as the core material for his ‘interventions’, his deconstructed sculptural installations. Over a four month period, Matta-Clark transformed the two storey weatherboard New Jersey house, splitting its facade and internal structures, thus conflating the psychologically house with the ‘new’ physical house. Matta-Clark reconfigured what this house was; from a modest family home into a culturally charged sculptural installation. Both the physical cut-open house and its title Splitting evoked the ‘universal’ loss of habitat, the disintegration of the family unit, and the erosion of the ‘American Dream’. Matta-Clark was acutely aware of the social inequalities in New York at the time, especially regarding housing and his intervention was in part, part of his social activism. Matta-Clark would have also been extremely aware of Hans Haacke’s controversial 1971s work, Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, Real-Time Social Systems May 1, 1971. This work consisted of photographs of substandard dwellings with accompanying texts about the New York landowner and landlord Shapolsky who owned and rented more slum buildings than anyone else in New York. Ironically, the New Jersey house that Matta-Clark ‘split’ belonged to his art dealers Holly and Horace Soloman, and as mentioned previously “the tenants had been abruptly evicted”. While Thomas Crow noted, that in order for Matta-Clark to start his cutting “the appliance and other debris left behind by its last African-American tenants were relegated to the basement”.(4) Art over life.

Hans Haacke: Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, Real-Time Social Systems May 1, 1971

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Image Source:www.macba.cat/en/shapolsky

Matta-Clark also played with space dis-orientations. Visitors to the New Jersey house were unnerved by the instability of the structure and felt discomforted by the widening gap and the ‘falling away’ of the back section of the house as they walked through the building. But fundamentally Splitting was about ideation and process. The idea of splitting a house in two and the physical deconstruction of the objet trouvé, being of paramount importance. Many artist around this time were investigating art that existed outside the gallery or museum culture, that was ephemeral, non-collectable and thereby of no monetary value. Splitting fitted into this philosophy well, as it only survived in its transformed state for a few weeks before the structure was totally destroyed and the site cleared.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s “[w]ar, political and racial assassinations and street riots, conflict between generations, all contributed to the feeling that a new order was evolving”. (5) There was a desire for artistic freedom, and a desire for more open and pluralistic societies. The Anarchitecture Group, to which Matta-Clark belonged, was a disparate group of New York artists who meet for about a year philosophising on the state of being, prior to staging a collaborative exhibition titled Anachitecture in 1974. This exhibition “encapsulated their critique of the modernist impulses of contemporary culture within which architecture was conceived as a symbol for that culture's worst excesses and drawbacks”.(6) Though, in the words of Caroline Gooden long time friend “anarchitecture was a work in progress in Gordon’s mind”.(7) For Matta-Clark the manifestation of ‘anarchitecture’ was the deconstruction of structures, “to reveal aesthetic, philosophical, and social problems”. (8) However, Matta-Clark’s involvement in the cutting of the ice for Dennis Oppenheimer’s Beebe Lake Ice Cut, Ithaca New York, 1969 must have stayed with him and influenced his decisions to start ‘cutting’, coupled with the new found joy of cutting/demolishing and its inherent danger. In the Beebe Lake scenario the ice was extremely thin. And according to Manfred Hecht “[i]t was always exciting working with Gordon - there was always a chance of getting killed. That’s what I liked”.(9) Matta-Clark took physical risks in achieving his interventions.

Artist Dennis Oppenheim and Cornell students create an ice channel in Beebe Lake as part of the 1969 "Earth Art Exhibition."

Image Source: Richard Clark/Courtesy Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art http://aap.cornell.edu

Nevertheless, he was a highly intelligent, complex, driven artist; a sculptor, film maker, photographer and draughtsman. He was ‘art royalty’. He was the son of Roberto Matta the renowned surrealist painter and the godson of the father of conceptualism Marcel Duchamp. He worked internationally and understood how the art world and the art market worked. Thus he understood the importance of documenting and publicising his ephemeral works. As the artist, friend and one time Anarchitecture member Richard Nonas noted:

Matta-Clark carries out the planned cut [in reference to Splitting] photographs it, invites the public in, then sinks one half of the house, photographs it again and invites inspection before cutting out the four corners of the house, exhibiting these in a gallery, producing a book about it and so on”. (10)

Gordon Matta-Clark:Conical Intersect 1975

Image source: www.e-flux.com courtesy David Zwirmer N.Y. and Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark

Another intervention of Matta-Clark’s was his Conical Intersect 1975. This project, part of the Paris Biennale of 1975, took place in a soon to be demolished pair of 17th century townhouses in Les Halles, Paris, to make way for the redevelopment of the Pompidou Centre precinct. Matta-Clark cut a number of circles out of the floors, throughout and across these adjoining buildings, revealing the pre-existing floors while also offering the street level observer vistas up and out of these historic buildings. Matta-Clark understood the significance of the buildings he was working on and of the controversy surrounding the Pompidou centre as cultural/urban renewal. Hence this deconstruction was duly watched and discussed by the local Parisians. Whether they agreed with the ultimate demolition of these buildings, this was a once in a life time opportunity of observing historic buildings being transformed into a temporary art work. For Matta-Clark this was a serious and conscious performance piece.

Gordon Matta-Clark: Concial Intersect 1975

Image Source: www.artnet courtesy David Zwirner N.Y. and Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark

Artist Dan Graham wrote:

by making his removals something like a spectacle of a demolition for casual pedestrians, the work could function as a kind of ‘agit-prop’ something like the acts in 1968 of the Paris Situationists, who had seen their acts as public intrusions or ‘cuts’ in the seamless urban fabric. The idea was to have their gestures interrupt the induced habits of the urban masses ... And make them aware of how urban space was used.(11)

In 1976 Matta-Clark’s twin brother Sebastian suicided and he, Gordon died of cancer three years later. Whether sensing his own mortality around 1975 Matta-Clark started working with his photographs in a calculated collaged manner. According to Nonas, “[h]e thought they [the photographs] had to be beautiful to survive as art”. (12) Obviously Matta-Clark desired to leave an artistic legacy of ‘cut-outs’, films, videos, photographs and his personal dairies.

Gordon Matta-Clark: Concical Intersect 1975

Cibachrome 101.7 x 76cm.

ImageSource:http://historyoftheworld.com

Courtesy Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark

The last work Matta-Clark did was a commissioned work for the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art. Between their modernist gallery building and their bluestone building stood a townhouse, which was to be demolished. Thus this became Matta-Clark’s last ‘internalised’ deconstruction. The year was 1978 and the work was titled Circus - The Carribean Orange. But Matta-Clark had moved on conceptually from the physical cuttings, so this last work was in ways a frustration, a holding back of his burgeoning new ambitions of cable and net works and tunnels.

However satisfying the final result - and there can be no doubt that Circus was a consummate work of both sculpture and frozen [it snowed heavily during deconstruction] theatre - the Chicago cutting did not extend his vocabulary or his capabilities, as the cable -and-mesh structure might have done. [Nevertheless] Circus did provide him with an even richer palette for new pieces of photomontage, enthusiasm for which he had tried to transmit to the Chicago curators ... “[t]hese large prints combine a new color vocabulary I have developed and will continue to evolve as a real part of my work”. (13)

Gordon Matta-Clark died in the August of 1978 aged 35.

RACHEL WHITEREAD

Rachel Whiteread: House 1993

Image source: www.image-identity.en/artists_images_folder/england/rachel-whiteread

Rachel Whiteread’s House is the quintessential objet trouvé house sculpture of recent contemporary art. Whiteread, the winner of the prestigious Tate Prize for 1993 had been commissioned by the London based Artangel Trust, to build her House, which existed from 25th. October 1993 to the 11th. January 1994.

House the monument, was the internal spaces that were cast in concrete from the outer shell of a remaining row-house, that was scheduled to be demolished, in Grove Road inner London. The old outer house walls were removed to show the new inside-out house. Andrew Renton, writes that House “draws the space around it to itself. It plots the stages of architectural and civic ideology; the social construction of housing and its gradual revision and supplanting”. (14) This idea of revision and supplanting, of urban re-newel and of the re-allocation of people, families and entire neighbourhoods for ‘their own good’, is the continuing mentality of many urban planners and city councils. These designers and social planners seem ignorant of the spirit of place, of a sense of community and of the extended family, as evidenced in long standing communities like Grove Road.

The reality that was House, is largely known only through articles and photographs, as this project existed for a mere three months. Therefore, the general perception of this monumental sculpture can only be learned not experienced. House was a solitary, concrete bunker - a three storey introverted house without the traditional pitched, gabled roof. It stood forlorn and alone, in its newly cleared streetscape. The obvious interiority of this monument is evident. On the sides of this pseudo-building are the reminders and remnants of the old adjoining walls revealing their reversed recesses, fireplaces, windows and doors.

Rachel Whiteread: House

Image Source: www.blog.southebys.institute.com

In his article on House, Stuart Morgan writes that:

[t]he major achievement of House was its ability to evoke interiority even as it seemed to banish every trace of inner life and mediation. The result was a monument which served to show how few monuments fulfill their true function: to call to mind, to pacify, to promote reverie, to act as a replacement, however wretched, for what has been lost. A point in time and space, it stopped visitors in their tracks to remind them of larger, deeper, simpler issues of life than their daily routine may include; issues they took for granted. In this case the ideal not of a house as a building but of belonging in general”.(15)

Morgan’s sentiments resound in the experiences of the Parisian pedestrians to the site of the 17th. century town houses being ‘renovated’ by Matta-Clark prior to their ultimate destruction. These houses revealed the passage of history, of a previous less complicated time and another lost part of Parisian social and architectural history.

Those interrelated concepts of things lost and of belonging. In Heidegger’s philosophy the sense of not belonging to an environment, a locale, and/or a house leads to the feelings of being psychologically ‘lost’. Heidegger used the inter-relationships between the words ‘habit’ and ‘habitat’ to show that “man knows what has become accessible to him through dwelling” by habit and that ‘dwelling’ means and implies a specific place, the habitat.(16)

Morgan went on to conclude, in his article on Whiteread, that House represented:

[a] period, a way of living, a family life, a community, a neighbourhood, a friendship ...To local residents, many of whom had lived in the area during wartime, House was the graveyard of all this; a sealed bunker like an overgrown vault, ... but the idea of monuments is to preserve certain issues in the mind, issues for which no easy resolution can be found. In other words, Whiteread’s chosen task [was] to try to touch the collective consciousness. (17)

Architecture is a social art, while the visual arts are generally a private form of self expression, but sculpture often unites the two.

CLAIRE HEALY AND SEAN CORDEIRO

Healy and Cordeiro: Cordial House Project (Process) 2003. Front of House and Vacant Lot

Photograph by Liz Ham 2003

Image Source: www.claireandsean.com/cordial_home.html

One of the first collaborative works by the Australian artists Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro could be seen as extending Matta-Clark’s oeuvre in their 2003 work the Cordial House Project. Healy and Cordeiro painstakingly dismantled a weatherboard house that has been listed for demolition and reconfigured it into a layered rectangular sculpture at Artspace in Sydney. As Russell Storer writes, “the elegantly ordered strata of Cordial House Project rendered a demolished suburban house as a massive sculpture of almost archaeological significance”.(18) The entire structural components of the house, the roofing tiles, the roofing and wall struts, the external wall cladding, the doors, windows, the architrave's were all disassembled and then laid layer upon layer to form a large rectangular sculptural form. This intriguing bulky structure exhibited at Artspace, was a conversion within a conversion. Cordial House Project was a house converted into an art object, being exhibited in a warehouse that has been converted into an exhibition space. Artspace has its own story of a past life in a more industrial age, thus there existed the juxtaposition for the viewer of concurrent possibilities of contemplating both home and industry. Sadly, like Matta-Clark’s work Cordial House Project had a short life in its reconfigured form, as it was to be truly ‘demolished’ at the end of the exhibition period; to live on in photographic form only.

Matta-Clark had used soon to be demolished houses to illustrate his dissatisfaction with the rental and housing market, the inner urban renewal, both in New York and Paris during the 1970s. So too are Healy and Cordeiro, in their own subtle way, commenting on the unfairness of the prevailing rental and housing markets in Australia and of the redundancy of past treasured homes, in the newest of gentrification and urban renewals.

Healy and Cordeiro: Cordial House Project, Installation

Photograph by Liz Ham

Image Source: www.claireandsean.com/cordial_home.html

Storer writes

:

Arising from their own experiences as artists living and working in inner-city Sydney, Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro’s work investigates the functions, processes and life cycles of buildings: construction, marketing, buying and selling, shifting tenancies, garbage removal, demolition and decay. The material and contents of buildings provide the stuff of their art as much as the exchanges, histories and meanings imbued within them”.(19)

Another objet trouvé work by Healy and Cordeiro that re-configures what a house is or might be, is Not Under My Roof 2008. This work is different from the others discussed as it is not an ephemeral work; it is a museum piece, a collectable, purchasable art work. This audacious work is the complete floor of a Queensland bungalow, hung like a giant painting, with the various floor coverings acting like abstracted painted sections. To have reduced an entire house to its structural floor only, is an ‘absurd’ and painstaking process. As the artist John Baldessari stated in reference to Matta-Clark, “Gordon ’s work spotlights and pinpoints one of the crucial ideas of modern art ... actually doing and redoing an absurd idea”.(20)

Healy and Cordeiro: Not Under My Roof (2008). Queensland Art Gallery

Site-specific work for Contemporary Australia: Optimism Queensland Art Gallery || Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane.

Image Source: www.claireandsean.com/works/not_under_my_roof. html

Matta-Clark played with space dis-orientations and in ways Not Under My Roof equally plays off a similar disorientation in that the viewer has to cognitively realign the entire floor into a wall sculpture/painting. This work inverts Matta-Clark’s statement about “[w]hy hang things on a wall when the wall itself is so much more a challenging medium?”.(21) Not Under My Roof is of course a verbal pun, there is no longer a roof over this floor and the floor now exists on a wall. Matta-Clark would have enjoyed the Duchampian joke!

These works by Healy and Cordeiro differ from the interventions of Matta-Clarke and Whiteread’s House, in that they are designed to be art gallery installations. Not that Matta-Clark did not exhibit his ‘cut-outs’ in museums. He stated that:

[a]spects of stratification probably interest me more than the unexpected views which are generated by the removals - not the surface, but the thin edge, the severed surface that reveals the autobiographical process of its making. There is a kind of complexity which comes from taking an otherwise completely normal, conventional, albeit anonymous situation and refining it, retranslating it into overlapping and multiple readings of conditions past and present. Each building generates its own unique situation.(22)

Gordon Matta-Clark: Bronx floors 1972-1973

Image source: Museum of Modern Art Collection N.Y.

These artist and their works span over forty years and show the changing aesthetic, the changing art world concerns, the changing political, social and economic realities that effected each decade, each era. Though, they show a cross generational creative synchronisticity. As the exteriority of the house, the wall between the private and the public, still serves as a starting point for artists.

The power of the work we see in museums is exactly this. It is the authenticity of the cultural production of a human being connected to his or her historical moment so concretely that the work is experienced as real; it is the passion of a creative intelligence to the present, which informs both the past and the future. It is not that the meaning of a work of art can transcend its time, but that a work of art describes the maker's relationship to her or his context through the struggle to make meaning, and in so doing we get a glimpse of the life of the people who shared that meaning. [A] work of art must be so singularly the concrete expression of an individual (or individuals) that it is no longer simply about that individual, but rather, is about the culture that made such expression possible.(23)

(Joseph Kosuth 1982).

.

End Notes:

(1)Brandon Taylor, The Art of Today, The Orion Publishing Group, London. 1995, p.33.

(2)John Berger, 1974 “Understanding Photography” The Look of Things, Viking, NY, p.3.

(3)Jane Carsten and Stephen Hugh Jones (eds.) About the House, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1995, p.2.

(4) Thomas Crow as cited in Corinne Deiserens, 2003 Gordon Matta-Clarke, Phaidon Press, London, p.74

(5) Michael Danoff as cited Mary Jane Jacobs, 1985 Gordon Matta-Clark: A Retrospective (Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art), p.6.

(6) http://www.spatialagency.net/database/the.anarchitecture.group

(7) James Attlee, 2007, Towards Anarchitecture: Gordon Matta-Clark and Le Corbusier,

Tate Papers, p.3.http://www.tate.org.uk/download/file/fid/7297

(8) K. Stills and P. Selz (eds.) 1996 Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art, University of California Press, Berkley p.505

(9) Manfred Hecht as cited in Corinne Diserens (ed) Gordon Matta-Clark, Phaidon Press, London 2004,

p.77

(10)ibid., p.140.

(11) Dan Graham as cited in Irving Sandlers, 1996 Art of the Postmodern Era: From the late 1960s to the early 1990s, p.69.

(12) Richard Nonas as cited by Corinne Diserens (ed) Gordon Matta-Clark, Phaidon Press, London 2004, p.143.

(13) ibid., p. 126.

(14) Andrew Renton, 1994 ‘House’ Art and Text #47, Art & Text Pty. Ltd., Paddington N.S.W. p.59.

(15) Stuart Morgan, ‘House’, Rachel Whiteread Shedding Light, London Tate Gallery Publishing, London. 1996, p.26.

(16) Christian Norberg-Schultz, Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture, Rizzoli International Publishers Inc. New York. 1980, p.22.

(17) Stuart Morgan, Rachel Whiteread: Shedding the Light, p.28.

(18) Storer, R. Introduction, Home Invasion, works by Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro, 2003 Artspace Visual Arts Centre Ltd., Sydney, p.7

(19) ibid., p.5.

(20) John Baldessari as cited by Irving Sanders,1996 Art of the Postmodern Era: From the Late 1960s to the Early 1990s, New York, Icon Editions, p.70.

(21) Corinne Diserens,(ed.) 2004 Gordon Matta-Clark, Phaidon, London, p.188.

(22) ibid., p.188.

(23) Joseph Kosuth as cited by Irving Sanders,1996 Art of the Postmodern Era: From the Late 1960s to the Early 1990s, New York, Icon Editions, p.xxvii